CREATIVITY, CHANGE, AND INNOVATION BLOG

Why Innovation Should Be More Like Holiday Wreaths

What a hot glue gun and a strategy session have in common…

Sharon, a corporate HR leader, spends her days managing her team and helping shape a culture

that supports innovation and creative thinking. But when fall rolls around, her evenings are

spent with foam wreath forms, mesh ribbon, and a glue gun.

She makes holiday wreaths. Bold ones. Glittery, whimsical, full of unexpected combinations.

Sometimes they land. Sometimes they don’t. But always, the process is messy, iterative, and

deeply creative.

It might sound like an odd crossover. But the parallels are powerful, and important. Wreath-

making is creative thinking in action. There’s a clear purpose, a loose set of tools, and a whole

lot of unknowns in between. There are aesthetic choices, design constraints, customer needs,

and constant course correction.

In many ways, it’s everything innovation in business should be, but often isn’t. Because in

corporate environments, creativity gets over-engineered. There’s pressure to skip the messy

middle. To justify every move in advance. To have the answer before asking the question.

But that’s not how creativity works. And it’s not how innovation thrives.

This kind of messy, iterative, hands-on thinking, the kind that mixes structure with

improvisation, is exactly what organizations need more of. Especially in complex, high-stakes

environments where creativity can too easily be dismissed as risky or indulgent.

Here are six leadership lessons from a wreath-making table that translate directly to the

boardroom, the brainstorming session, and the strategy retreat.

Lesson 1: Creativity Needs Chaos Before Clarity

Most wreaths start ugly.

At some point in the design, the composition looks off. The ribbon is fighting the florals. The

texture balance is wrong. The whole thing feels like a misfire.

But that’s part of the process. Keep going, keep layering, keep stepping back. Eventually,

something clicks.

Creative thinking at work follows the same pattern. Early drafts are disjointed. Brainstorms feel

chaotic. A new idea might solve one problem but create another. And it’s tempting to pull the

plug.

Visionary leaders know that clarity follows chaos, not the other way around. The mistake most

teams make is stopping too soon.

Lesson 2: Leaders Compose, They Don’t Control

Wreath-making isn’t about wrangling every element into submission. It’s about noticing how

different materials interact. Where the eye travels, how the shapes and colors work together,

and what needs to shift.

It’s not control. It’s composition.

The same applies to leading innovation. The role of the leader isn’t to dictate every move, it’s to

shape conditions. To arrange talent. To provide structure and space. To edit when necessary and

step back when not.

Too many leaders default to micromanaging creative work out of fear. But possibility can’t be

coerced. It has to be composed.

Lesson 3: Reward the Risk, Not Just the Result

When a wreath is finished, it gets photographed, complimented, maybe sold.

But the real learning comes from the ones that didn’t work. The ones where the wire frame

sagged or the colors clashed. Those failures sharpen instinct and improve judgment.

Innovation cultures that only reward the polished end product create team members who play

it safe. Especially in industries where risk aversion is built into the operating model, the instinct

to avoid failure is understandable, but it’s also limiting.

Leaders who want to unlock creativity have to reward effort, curiosity, and experimentation

before the outcome is clear. Celebrate learning. Normalize iteration. Make creative courage

visible.

Lesson 4: Presence Is a Strategic Skill

At a recent holiday market, Sharon noticed something.

Some wreaths drew people in immediately. Others got passed by. But unless you were paying

close attention, to body language, to facial expressions, to where people paused, you’d miss it.

That’s a core skill of innovative leadership: attention.

The best leaders are present. They notice micro-signals. They see when energy dips in a

meeting. They pick up on which ideas generate buzz and which ones die on the table. They

watch for friction, momentum, hesitancy, not just hard data.

Creativity is a perceptual skill. Leadership is, too.

Lesson 5: Perfectionism Kills Possibility

Ask a toddler to decorate something, and they’ll dive in with joyful abandon. Stickers go in odd

places. Colors clash. There’s no blueprint; just curiosity and confidence.

Now watch adults in a meeting asked to "be creative." They freeze. They overthink. They edit in

real time.

Perfectionism has been trained into them.

Visionary leaders understand that innovation requires unlearning this habit. They create

environments where teams can explore, test, even get a little weird. Without judgment. They

separate idea generation from evaluation. They know that play isn’t childish; it’s strategic.

In high-stakes environments, this may feel radical. But it’s precisely what’s needed. Because the

absence of risk-taking is not safety; it’s stagnation.

Lesson 6: Feedback Beats Forecasting

When Sharon set up her table at the night market, she wasn’t just hoping for sales. She was

running an innovation lab.

She watched what caught attention. She listened to what sparked conversation. She noted what

got ignored. It was real-world feedback in real time; fast, human, unfiltered.

Leaders often over-rely on sanitized data. But some of the richest insights come from

interaction. Like from putting a prototype in the world and seeing what happens.

This might look like piloting a new workflow in one department, testing a communication tool

with a focus group, or introducing a new service model with opt-in participation.

The point is to test. Learn. Refine. Then scale.

Wreath-making may seem like a strange metaphor for business innovation. But that’s the point.

Innovation doesn’t come from more of the same. It comes from unexpected combinations.

From letting the messy middle exist. From leaders who know that vision isn’t about having all

the answers; it’s about clearing space for something new to emerge.

Possibility isn’t a process. It’s a posture. And it starts with leaders willing to get glitter on their

hands.

The Secrets of Visionary Leaders: Who Think Possibility Before Productivity

Productivity looks good on paper. It’s measurable. It’s visible. And in many organizations, it’s worshipped. But here’s the problem: productivity isn’t the same as progress.

Many cultures confuse motion with momentum. Leaders celebrate packed calendars, rapid responses, and efficiency hacks, but often fail to ask whether all that movement is

taking them somewhere that matters.

That’s why visionary leaders think differently.

They think in terms of possibility, not just productivity.

Visionary leaders understand that creative thinking doesn’t thrive in a culture obsessed with output. It requires white space. It requires permission. And most of all, it requires a

culture that rewards curiosity as much as completion. Let’s be clear: this isn’t an anti-productivity argument. High-functioning organizations absolutely need discipline,

systems, and execution. But when those become the only things that are recognized, something vital gets lost: the capacity to imagine what could be.

When you reward only productivity, you get compliance. When you reward possibility, you get transformation. And possibility doesn’t happen by accident; it’s cultivated. It requires

leaders to step back and ask not just what their teams are doing, but what they're allowed—and encouraged—to think about. In cultures built around possibility, it’s normal to

wonder out loud. It’s normal to challenge what’s always worked. It’s normal to say, “Let’s try something completely different,” without needing a spreadsheet to justify it.

Here’s how visionary leaders shape cultures that elevate possibility without sacrificing

performance:

Track Curiosity, Not Just Completion Most cultures track deliverables and deadlines but never

measure how often someone asks a provocative question, reframes a challenge, or proposes a

completely unexpected solution. Visionary leaders design metrics that reflect their priorities.

They create space to ask, “Are we thinking differently, or just doing more of the same?” They

evaluate not just the speed of delivery, but the originality of approach.

Model Curiosity in Public When senior leaders ask questions they don’t have answers to, and

do so visibly, they send a signal that exploration isn’t a weakness. It’s a strength. Possibility

thrives when leaders say, “I don’t know, but I’d love to find out,” or “What haven’t we tried

yet?” That posture becomes contagious. And when it’s reinforced by real follow-through, not

just rhetoric, it creates lasting cultural permission.

Slow Down on Purpose Fast isn’t always better. Visionary leaders create intentional pauses for

reflection; team time to step back, question what’s driving the work, and explore alternate

paths. This might look like a challenge-framing session, a wild idea jam, or a thinking retreat

without an agenda. These spaces shift the default from autopilot to agency. And often, the most

valuable ideas surface when no one is overtly trying to be productive.

Spotlight Exploration, Not Just Execution In most organizations, the person who gets the most

done wins. But visionary leaders notice and acknowledge the person who asked the question

that redirected the project or surfaced a bold new idea. They don’t wait for quarterly results to

measure value; they look for creative contributions in the moment. Recognition isn’t just about

what got finished. It’s about what got imagined.

Design the Culture, Don’t Just Describe It Cultures aren’t changed by willpower. They’re

changed by structure. Visionary leaders adjust expectations, language, and workflows to

reinforce the behaviors they want to see. That might mean fewer status meetings and more

divergent thinking sessions. It might mean swapping “What’s the update?” for “What are we

learning?” It might even mean incentivizing questions instead of answers. They remove friction

for reflection, and clear a path for creativity.

Build Thinking Into the Workflow Visionary leaders don’t treat creative thinking as something

that happens off to the side. They embed it into how work gets done. That might mean starting

meetings with generative questions instead of status updates. It might mean using tools that

prompt reframing before problem-solving. It might mean allocating time in project cycles for

idea expansion before decision-making. When creative thinking is built into the actual flow of

work, it becomes a natural reflex, not a separate event.

The result of all this? Not just better ideas, but a more adaptive, resilient, and future-ready

organization.

One where innovation isn't a one time event but a cultural norm. One where people aren't just moving fast, they're moving forward.

And let’s be honest: this shift doesn’t happen overnight. It requires unlearning

deeply ingrained habits, especially for high achievers who’ve built careers on getting things done. The hardest part of possibility-driven leadership is often letting go of the illusion

that productivity equals value. Visionary leaders model the change they want to see before they ask anyone else to do it.

They resist the pressure to fill every moment with output. They normalize reflection. They make time for idea generation and inquiry and protect it like they would any other

strategic asset. They also help others do the same. They train teams to get comfortable with ambiguity, reward experimentation even when it doesn’t pan out, and treat creative

thinking as a daily necessity, not an extracurricular. Because when the work becomes too much about the doing, the thinking disappears. And when the thinking disappears, so

does the future. If your culture only rewards productivity, don’t be surprised when people stop imagining what else is possible. Visionary leaders don’t just get more done. They get more done because they think differently first.

The Secrets of Visionary Leaders: Create Change Before It’s Urgent

Most leaders don’t ignore change because they don’t care. They ignore it because, in the moment, it doesn’t feel urgent. When the metrics look good and the operations hum

along, making time for possibility feels indulgent. But that’s precisely what separates the visionary

leaders from the merely competent: they make space to reimagine before a crisis demands it.

Visionary leaders don’t wait for pain to trigger change. They act when things still look fine on

the surface—when most people are coasting. They understand that comfort breeds complacency,

and complacency is where innovation dies.

So why is it so rare to see organizations making meaningful change when everything’s

"working"?

Because change feels riskier than routine. Leaders are rewarded for short-term outcomes, not

long-term possibility. Teams are trained to fix problems, not to explore potential. And entire

cultures are built to preserve stability—not to challenge it.

But possibility doesn’t live in the stable. It lives in the slightly unhinged questions that start with

“What if we…” or “Why don’t we…” or “Wouldn’t it be wild if…” It lives in the willingness to

step off the well-paved path and consider what might lie just beyond the familiar.

Visionary leaders don’t just tolerate this kind of thinking—they create the conditions where it

can thrive. They reshape the cultural assumptions that say, "Don’t rock the boat," and replace

them with, "Let’s see what else is possible." They interrupt the patterns that reward efficiency

over imagination. They normalize exploration without the guarantee of immediate ROI.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

· They carve out space for thinking, not just doing. They understand that innovation isn’t a

task to check off—it requires mental white space, uninterrupted time, and freedom from constant

urgency. Visionary leaders protect this space intentionally, creating boundaries that allow their

teams to go beyond surface-level thinking. They don’t just suggest it—they schedule it. They say

no to unnecessary meetings, protect thinking time on calendars, and give teams permission to

pause, reflect, and reframe. They make deep thought as non-negotiable as budget reviews.

· They ask their teams to challenge assumptions even when there’s no problem to solve.

Because waiting for problems means you're always reacting—never inventing. This isn’t about

chaos for chaos’ sake—it’s about building a muscle for questioning the status quo, even when it

feels comfortable. Visionary leaders embed assumption-checking into regular conversations.

They model the question, “What are we treating as true that might not be?” and invite alternative

perspectives to surface before consensus locks in. They understand that asking good questions is

a creative act in itself.

· They shift language from certainty to curiosity. Questions like “What if…” and “Why

not…” become signals of forward momentum, not distractions from the agenda. Over time, that

language shift rewires team dynamics: fear of being wrong is replaced with enthusiasm for

exploration. Visionary leaders celebrate when a team member floats an odd idea or pushes back

on accepted norms. They replace "prove it" with "explore it," and open the door for discovery

instead of defensiveness. This linguistic shift creates an environment where new thinking is

expected, not exceptional.

· They reward experimentation before outcomes. Even small tests of new thinking are

celebrated—not for being right, but for being brave. Leaders build in mechanisms that value

curiosity over perfection, reinforcing that learning is part of progress—even when the result isn’t

tidy. Visionary leaders don’t just permit failure—they frame experimentation as a responsibility.

They track learning as a metric and ask after-action questions like “What surprised us?” and

“What will we try differently next time?” They view progress as cumulative, not instant.

· And most importantly, they model all of this themselves. When leaders practice what they

preach, they grant everyone else permission to step into possibility. They show—not just

tell—their teams that questioning, exploring, and stretching are part of the job, not threats to it.

They let people see them wrestling with ambiguity, changing their minds, and exploring ideas

without immediate resolution. They walk the talk of creative leadership, not by declaring vision,

but by visibly engaging with uncertainty. This kind of leadership makes possibility feel safe,

supported, and worth pursuing.

In environments like healthcare, pharma, or financial services—where the stakes are high and the

margin for error is low—it’s tempting to think that possibility has to take a backseat to

predictability. But in reality, those are the environments most in need of leaders who can see

around the corner.

Creating change before it’s urgent isn’t reckless. It’s responsible. It’s what allows organizations

to adapt instead of react. To lead instead of follow. To shape the future instead of surviving it.

If your team is only innovating when a fire breaks out, you’re not leading—you're firefighting.

Visionary leaders don’t wait for permission. They look beyond what’s working to see what’s

possible.

Your Brain is Lying to You (and it’s costing you breakthroughs!)

“You must fly the plane.”

That’s the 2025 AICC Chairman’s theme — and it’s exactly what leadership feels like right now. You’ve got priorities,

pressures, and people counting on you. You’re watching your market, your margins, your team. You’re flying

through turbulence, and the instruments keep changing.

But what if the biggest threat to your trajectory isn’t external? What if it’s how your own experience shapes what

you can no longer see?

When Experience Becomes a Blindfold

The Curse of Knowledge is a cognitive bias that happens when we become so familiar with something that we stop

examining it. Once we “know” something, our brains tag it as settled. We make it part of the mental autopilot.

That’s helpful for getting through a busy day. But it’s dangerous in an environment that demands change.

Here’s how it shows up:

∙“That’s how we’ve always done it.”

∙“We already tried that.”

∙“Our customers wouldn’t go for it.”

These aren’t facts. They’re filters — installed by past experience, running quietly in the background. We don’t

notice them because they feel like truth. But the real problem is that we stop questioning them.

The Curse of Knowledge makes it harder to see new solutions, new paths, and new ways to solve the new

challenges you’re facing.

And in a business like yours — where capital investments are big, timelines are long, and the market is in motion —

that can cost you dearly.

From Obstacle Thinking to Possibility Thinking

There’s a different way to lead through uncertainty. And it starts with possibility thinking.

Possibility thinkers don’t assume that the first roadblock is the end of the road. They’re willing to look again. To

question what seems fixed. To ask, “What else could be true?”

This isn’t wishful thinking. It’s disciplined curiosity.

And in industries that are balancing new tech, generational transitions, and growing complexity — curiosity is one

of the most underutilized competitive advantages available.

Here are three practical ways to break out of the Curse of Knowledge and shift from “obstacle” to “opportunity”:

1. Assumption Smashing

Most of what limits your thinking isn’t a real rule. It’s a made-up one. It’s created by your brain based on all your

past experience and expertise.

People absorb assumptions from their own history: what’s worked, what hasn’t, what got praised, what got shut

down. But just because something was true once doesn’t mean it’s true now.

Assumption smashing is the act of surfacing those invisible “rules” and breaking them on purpose.

In innovation sessions, it often takes just one bold move — and it shifts the entire room. Once someone questions

what others were treating as non-negotiable, it unlocks the permission to do the same.

One person’s reframing can become everyone’s breakthrough. As a leader, that person needs to be you. You go first — and show others that it’s not only allowed to question

assumptions, it’s expected.

2. Change the Question

If a team is stuck, the problem might not be the problem. It might be how it’s being defined.

Small changes in language lead to big differences in thinking. Let’s say the goal is to reduce customer churn. It could

be framed as:

∙“How can we retain customers?”

…or:

∙“How can we surprise our customers?”

∙“How might we create something they’d brag about?”

∙“What would make them stay, even if a competitor charged less?”

Each question sends the brain down a different path.

The goal isn’t to wordsmith. It’s to find the frame that leads to fresh possibility.

3. Borrow a Brain

Sometimes teams are simply too close to the problem.

That’s why bringing in someone who doesn’t “know how it works here” can be so powerful. They’re not stuck

inside the same patterns. They don’t carry the same assumptions.

Invite a colleague from another department. Pair up a veteran with a next-gen team member. Ask a new hire what

they see.

Fresh eyes can expose what the Curse of Knowledge has hidden.

You’re Already Flying. Just Don’t Forget to Check the Map.

Pilots check their instruments constantly. They don’t assume. They cross-check. They adjust course when needed.

As a leader, that same discipline matters.

The Curse of Knowledge isn’t a flaw. It’s a cognitive bias — a natural part of how human brains work. But it doesn’t

have to decide what’s possible. It can be challenged — and others can be led to do the same.

You’re already flying the plane.

Now ask yourself:

Are you still headed in the right direction?

The most dangerous limits are rarely external.

They’re the ones that go unquestioned

10 RULES FOR BRAINSTORMING SUCCESS

At various times, the popular press raises the idea that group brainstorming isn’t effective at generating creative solutions. That assertion is erroneous, for a variety of reasons. Groups can—and do—successfully brainstorm creative and useful solutions.

But research does show that effective brainstorming requires adherence to some specific guidelines. If it’s done casually, without guidelines, and the sessions are run by people with no knowledge of how to do it well, it will be significantly less effective than it could be.

It will either result in unrestrained chaos with no momentum to move the project forward, or it will just be plain boring (which also results in no momentum).

(And for those of you who know that brainstorming is only one technique in a creative thinking toolbox, please excuse the shortcut. Most people think of brainstorming as any idea generation, and that’s the way it’s used here.)

So, how do you set up your brainstorming sessions for success? Follow the rules. They will see you safely through the necessary level of chaos, to the strategic momentum you’re hoping for.

Free them from fear. It’s very difficult for people to share ideas if they’re concerned about possible negative consequences. A process and a setting that helps people get past fear are critical for brainstorming to be effective. One key principle in creating this setting is to prohibit any evaluation (even positive evaluation) during the idea generation.

Use the power of the group. Build, combine, and create new ideas in the moment. Don’t just collect ideas that people have already had. The building and combining is where the magic happens. Occasionally break up into pairs or small groups. This will encourage even more sharing and combining of ideas.

Get some outside stimulus. Asking the same group of people to sit in the same room and review the same information they’ve seen before is unlikely to result in exciting, new ideas. Talk to your customers, talk to other experts, explore how other industries are doing it. Have the meeting in the park or in a museum. Bring some toys into the room. There are countless ways to shake things up; try something new every time.

Encourage the crazy. Everyone has heard someone say at the beginning of a brainstorming, “every idea is a good idea.” And then there’s a collective eye roll because no one believes it. While it’s not true that every idea is a practical idea, it is true that every idea can offer useful stimulus for additional ideas. Sometimes those ideas that are tossed out as jokes can be the spark that leads to a new direction and a winning idea. Allow, encourage, and use every idea, even if only for creative fodder.

It’s a numbers game. The more “at bats” you have, the more likely you are to hit a home run. Drive for quantity of ideas. Ensure the session is long enough to generate lots. If you only spend 10 minutes on brainstorming, don’t expect great results.

Laugh a lot. Humor stimulates creativity, so let it happen. One easy way to start off a session; have everyone introduce themselves by answering a fun or silly question. One example you could use in the fall: “What’s something you DON’T need more of for the holidays?” Some of the answers could even start sparking real ideas for the session!

Homework is required. Both individual and group efforts are critical for success. Expect and insist on individual preparation in advance and follow-up afterward. Ensure everyone knows the goal in advance of the session, and ask them to do some homework before they arrive. When the session is over, create an action plan that allows ideas to continue to be shaped and added to as you move forward.

It’s not for amateurs. Effective brainstorming requires knowledge and skill, both to participate, and especially to facilitate. It’s a completely different set of techniques and expertise than running other meetings, don’t assume you can do it well just because you can run a great meeting. If you don’t have a facilitator in your team who has the skill to train the group and run the session, hire an external one, or get some training to develop the skills internally.

If it looks like a duck, but doesn’t act like a duck, it’s not a duck. If you can’t, or don’t intend to, follow the guidelines for successful brainstorming, then don’t call it brainstorming. For example, a meeting that just becomes a stage for one person to spout their ideas isn’t useful or engaging. And if brainstorming is not organized and structured appropriately, everyone in the room will feel how ineffective it is, and they’ll be sure to skip your next session. Either set up for success, or don’t bother.

You’re not done until you decide. You’ve all been in this situation; it’s the end of a brainstorming session, you’ve created a long list of ideas, and someone volunteers to type up and distribute the list. And ... that’s the end. There’s no action, or at least not that anyone is aware of. It’s fairly demotivating to spend time and energy generating ideas and then feel they went nowhere. Plan time for, and require the group to do, some prioritizing of ideas during the session. Spend at least an equal amount of time on converging as you do on diverging. Yes, you read that right. If you generate ideas for an hour, also spend an hour on selecting, clarifying, and refining ideas at the back end. If you leave the meeting with a huge list of potential ideas, that’s not success. You want to leave the meeting with a short list of clear ideas, and a plan for action on each of them.

Don’t let opportunities for growth bypass you

There’s an old adage that says people are resistant to change. There’s some truth in that. This can be challenging when you want to move a team forward to try new ideas. There is no perfect business. As the quote from author William S. Burroughs says, “When you stop growing, you start dying.” Fortunately, there are ways to help teams act on new ideas.

Understand, however, that people’s resistance is likely not something they’re consciously choosing. The expectation that change equals loss is, surprisingly, grounded in neuroscience. All humans have a set of cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that you use for problem-solving and decision-making.

There are a few things to understand about cognitive biases before you dive into why they’re problematic.

First, cognitive biases are not the same kind of bias related to diversity and inclusion initiatives. That’s a completely different concept. Cognitive biases are a neuroscience concept about how our brains operate.

Second, cognitive biases are not We all share the same cognitive biases. It is not as if you have one cognitive bias and somebody else has a different one. We share these same mental shortcuts.

Thirdly, cognitive biases operate subconsciously. You are not aware you’re relying on these shortcuts.

People tend to shy away from truly new ideas and opt for the safest choices. It’s because of a mental shortcut that says change invites risk. It’s due to a specific cognitive bias called the status quo bias.

How the status quo bias works

The status quo bias is that you instantly and subconsciously presume change to mean loss. You assume that the current state of affairs is the best, and anything other than that will be negative.

So, when you’ve asked a team to look for new ideas and then consider the options, people tend to choose the safest, most incremental and least disruptive ideas. In other words, they lean toward the least amount of change possible.

What to do when change is needed

There are situations when change is needed, such as when new government regulations go into force or you can’t see clients in person. Never making changes causes businesses to flounder. Ensure that those whose buy-in you want don’t let the status quo bias get in the way of considering problem-solving ideas.

Here are some tips to help you get around the status quo bias:

Emphatically include in your list of criteria that you want ideas that are disruptive, new and will make a significant impact. Clearly stating that as a criterion will make a difference and will remind people that they need to explicitly consider some of the more interesting, unique and potentially harder-to-implement ideas.

Require the group to list the potential downsides of changing nothing. Changing nothing is a decision. And, unfortunately, it is often the decision made by default. There are times when the window of opportunity shuts. So, when a group decides not to decide, they need to consider the true consequences of that decision. Given, though, that they thought they needed to meet and develop new ideas, there’s already a feeling change is needed.

To become a more visionary and creative leader, you must ensure that new, interesting and more challenging ideas get real consideration. And your team needs assistance so they can do the same. These tips for getting around the status quo bias will help your team consider the potentially more disruptive ideas you may need to fundamentally solve the challenge at hand and help your business thrive.

The Secrets of Visionary Thinkers: How to ensure new ideas get real consideration

When you think of famous visionary leaders, you often think that they have something, know something, or do something that the rest of us don’t have, don’t know, or can’t do. The truth is, they don’t. The only thing they have is an intuitive understanding of how to open their minds and consider new ideas.

When you’re thinking about new ideas, you’re often thinking of the divergent phase of the brainstorming process – where you generate many new ideas.

However, the convergent (deciding) phase is equally important – to ensure that those new, fresh, and interesting ideas thought of during the divergent phase actually get considered. Due to some basic neuroscience principles, it’s all too easy to instantly reject any truly new ideas. The very human tendency is to decide to select the ideas that make you feel the least uncomfortable. In other words, even if you managed to generate some really unique and innovative ideas, you’re actually fairly unlikely to decide to use them, unless you do some overt things to help overcome instinctive fears of anything new.

There’s an old adage that people are resistant to change. There’s some truth in that, most people are a bit resistant to change in most circumstances.

However, there are many instances where change is embraced with open arms. Events like marriage, the birth of a child, a career change, or moving to a new city are all dramatic life changes that are typically welcome. Most people are happy and excited to embark on these new journeys.

So, what is it about other types of changes that make the “people don’t like change” adage true? The difference is, with a few exceptions like the above, change is typically assumed to be negative.

To better understand this, think about this hypothetical situation. You’re at your desk, doing your work as usual, when your boss walks over and says, “Things are going to change around here”. If you’re like most people, your instant assumption is not that things are going to get better. You probably assume it’s going to be worse. That you will experience some loss of something you currently benefit from. Even if you can acknowledge that the change might be good for the department or the company, your go-to assumption is that things will be somehow worse for you personally.

This expectation that change equals loss is, surprisingly, grounded in neuroscience. All humans have a set of cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that you use for problem-solving and decision-making. There are a few things to understand about cognitive biases before you dive into why they’re problematic.

First, cognitive biases are NOT the same kind of bias related to diversity and inclusion initiatives. That’s a completely different concept. Cognitive biases are a neuroscience concept; they have to do with how our brains operate.

Second, cognitive biases are not individual. All humans share the same cognitive biases. It is not as if you have one cognitive bias and somebody else has a different one. All humans share these same mental shortcuts.

Thirdly, cognitive biases operate subconsciously. You are not aware you’re relying on these shortcuts when you are.

When it comes to the convergent phase of creative thinking – when you’re voting and deciding from a large list of ideas – the cliche that people don’t like change tends to hold true. You tend to shy away from the truly new ideas and only vote for the “safest” ideas.

This tendency is due to a specific cognitive bias called the Status Quo bias.

The Status Quo bias is the phenomenon just described – that you instantly and subconsciously presume change to mean loss. Specifically, loss to you personally and individually. You assume that the current state of affairs is the best, and anything other than that will be negative.

So, when you are looking for new ideas and have generated a list of possibilities, and it is time to choose among them, you tend to choose only the safest, most incremental, and least disruptive ideas. In other words, you lean toward the least amount of change possible.

But suppose the situation is something that actually needs real change. In that case, you need to ensure that the team making the decisions doesn’t let the status quo bias get in the way of considering a more radical idea, which may be the one that really solves the problem.

Here are some tips to help you get around the status quo bias.

1.) Overtly include in your list of criteria that you want ideas that are disruptive, new, and will make a significant impact. Clearly stating that as a criteria will make a difference and will remind people that they need to explicitly consider some of the more interesting, unique, and potentially harder-to-implement ideas.

2.) Another way you can approach getting around this status quo bias is to require the group to list the potential downsides of changing nothing. Changing nothing is a decision. And unfortunately, it is often the decision that is made by default. You can all too easily “decide to decide later” once you have more information. And then during the next meeting, you decide again to decide later, once you have even more information. And you continue that cycle until you miss the window entirely, and it’s too late. So, when a group decides not to decide, they need to consider the true consequences of that decision. Given that they thought there was a need to get together and develop new ideas, there’s likely a definitive reason to create change by selecting a more impactful idea.

In order to become a more visionary and creative leader, you need to personally ensure that new, interesting, and more challenging ideas get real consideration. And you need to give your team some assistance so that they can do the same. These tips for getting around the Status Quo bias will help your team truly consider the potentially more disruptive ideas you may need to fundamentally solve the challenge at hand.

Overcoming the Curse of Knowledge to Inject New Ideas Into Your Business

When we think about famous visionary thinkers, we subconsciously assume that they have some magic characteristic that the rest of us don’t have or can’t achieve.

In reality, the only magic they have is an intuitive understanding of how to avoid some very common creative thinking blocks. One of those blocks is the “Curse of Knowledge,” a cognitive bias, or mental shortcut, that all humans share.

Stuck inside the box

You’ve probably heard the term “Thinking outside the box.” And you’ve probably, at some point in your career, been asked to think outside the box. But without any understanding of why the box is there or how it was created, it’s hard to know how to break out of it. The reality is that we each create our own “box” through this “Curse of Knowledge.”

To understand this concept, imagine for a moment that your task is to think of new ideas for salad dressing. Try to come up with a few in your mind right now.

Chances are, the ideas that came to your mind were incremental variations of existing flavors or ingredients. You may have thought of fruit-flavored dressing. Or spicy, chipotle dressing. Or perhaps dressing that’s flavored like your favorite cocktail. Or your favorite dessert. All really interesting ideas if you are only looking for ideas that don’t change the current nature of salad dressing, nor the way it’s currently manufactured, packaged, sold or used. But the task was to find new ideas for salad dressing. That challenge was not limited to simply new flavors, but your brain likely limited your thinking to mostly just new flavors.

Here’s why incremental ideas tend to be the first (and sometimes the only) kind of ideas to emerge. All humans rely on past knowledge to subconsciously try to shortcut problem-solving. We instantly — and subconsciously — call on everything we know from the past to come up with solutions for the new problem. While this ability to call on past learning is an incredibly useful trait in many situations (it’s one of the reasons we’re at the top of the food chain), when you’re looking for new ideas and solutions, it actually becomes a significant barrier. It limits your thinking to nothing but slight variations of what already exists.

The minute you saw the words “salad dressing,” your brain made a bunch of instantaneous assumptions that you’re likely not aware of. Those assumptions were probably things like these:

It’s stored in the refrigerator and served cold.

It’s used on lettuce.

It’s liquid.

Salad is eaten from a bowl or plate.

Salad is eaten with the fork.

Using the salad dressing challenge again, now assume one of the above “facts” does not have to be true. What ideas could you come up with then? You might think of ideas like these:

Salad dressing that you heat in the microwave (not cold).

Dressing for fruit, or for meat (not used on lettuce).

A powder whose full flavor is activated when it contacts the moisture of the lettuce (not liquid).

Salad dressing in the form of a wrap, so you can eat the salad on the go. (Salad isn’t served on a plate.)

Salad dressing in the form of an edible skewer. (Salad isn’t eaten with a fork.)

As you can see, the nature of the ideas that arise after crushing the embedded assumptions is dramatically different from the ideas that came before. That’s because your brain is no longer limiting your creativity with artificial guardrails that may not actually exist and that you weren’t even consciously aware of.

Interestingly, the more expertise you have in an area, the more of these limiting assumptions you have subconsciously embedded in your thinking. So as an expert in the drain cleaning and pipe rehab field, you likely have many embedded assumptions that you’re not aware of but that are likely impeding your creative thinking in a significant way.

The Cure

Fortunately, there is an antidote to the “Curse of Knowledge.” We have to consciously surface and challenge our hidden assumptions.

Step 1 — Surface your subconscious assumptions by generating a long list of statements that start with things like:

Well, in our business everyone knows…

We have to…

Our product is/does/has…

Well, of course…

We could never…

Be sure to list some really obvious, superficial, or seemingly trivial “facts,” observations, processes, etc. Sometimes breaking the obvious ones can lead to the most innovative ideas. For example, the fact that salad dressing is liquid seems fairly trivial. But breaking that assumption led to some truly breakthrough ideas.

Step 2 — Once you’ve come up with a long list, pick one that may not have to be true and start thinking of new ideas based on breaking that one. Then pick another and do it again. And again. You’ll amaze yourself with the innovative ideas you come up with.

Remember that the “Curse of Knowledge” is based on experience and expertise. Many people often assume that the best way to get new thinking, new ideas, and new solutions is to bring together a bunch of experts on the topic. But the reality is that all those experts will have a very similar set of subconscious mental frameworks. They’ll all have essentially the same “Curse of Knowledge.”

A better way to generate new ideas is to invite a few experts, and then several other people with different experiences, knowledge and perspectives. Those non-experts will help force the experts to confront and overcome their knowledge curse.

The “Curse of Knowledge” is a formidable adversary that exists in our brains all the time and hinders our visionary potential. But it’s possible to shatter the chains that confine our thinking and unlock the path to visionary breakthroughs.

The Secrets of Visionary Thinkers: Two simple steps to crushing subconscious assumptions

When we think about famous visionary thinkers, we subconsciously assume that they have some magic characteristic that the rest of don’t have or can’t achieve. But in reality, the only magic they have is an intuitive understanding of how to avoid some very common creative thinking blocks. One of those blocks is the Curse of Knowledge, a cognitive bias, or mental shortcut, that all humans’ share.

Stuck Inside the Box: The Curse of Knowledge

You’ve probably heard the term “Thinking outside the box.” And you’ve probably, at some point in your career, been asked the think outside the box. But without any understanding of why the box is there or how it was created, it’s hard to know how to break out of it. The reality is that we each create our own “box”, through this Curse of Knowledge.

To understand this concept, imagine for a moment that your task is to think of new ideas for salad dressing. Try to come up with a few in your mind right now – don’t skip ahead!

Chances are that the ideas that came to your mind were incremental variations of existing flavors or ingredients. You may have thought of fruit-flavored dressing. Or spicy, chipotle dressing. Or perhaps dressing that’s flavored like your favorite cocktail. Or your favorite dessert.

All really interesting ideas, IF you are only looking for ideas that don’t change the current nature of salad dressing, nor the way it’s currently manufactured, packaged, sold, or used. The task was to find NEW ideas for salad dressing. That challenge was not limited to simply new flavors, but your brain likely limited your thinking to mostly just new flavors.

Here’s why incremental ideas tend to be the first, and sometimes the only, kind of ideas to emerge. All humans rely on past knowledge to subconsciously try to shortcut problem-solving. We instantly – and subconsciously – call on everything we know from the past to come up with solutions for the new problem. While this ability to call on past learning is an incredibly useful trait in many situations (it’s one of the reasons we’re at the top of the food chain), when you’re looking for new ideas and solutions, it actually becomes a significant barrier. It limits your thinking to nothing but slight variations of what already exists.

The minute you saw the words “salad dressing”, your brain made a bunch of instantaneous assumptions that you’re likely not aware of. Those assumptions were probably things like:

Salad dressing comes in a bottle

It’s liquid

It’s stored in the refrigerator

It’s used on lettuce

Salad is eaten from a bowl or plate

Salad is eaten with a fork

Using the salad dressing challenge again, now assume one of the above “facts” does NOT have to be true. What ideas could you come up with then? You might think of ideas like:

Salad dressing that you heat in the microwave (not cold)

Dressing for fruit, or for meat (not used on lettuce)

A powder whose full flavor is activated when it contacts the moisture of the lettuce (not liquid)

Salad dressing in the form of a wrap, so you can eat the salad on the go (salad isn’t served on a plate)

Salad dressing in the form of an edible skewer (salad isn’t eaten with a fork)

As you can see, the nature of the ideas that arise after crushing the imbedded assumptions is dramatically different from the ideas that came before. That’s because your brain is no longer limiting your creativity with artificial guardrails that may not actually exist and that you weren’t even consciously aware of.

Interestingly, the more expertise you have in an area, the more of these limiting assumptions you have subconsciously imbedded in your thinking. So, as an expert in your field, you likely have MANY imbedded assumptions that you’re not aware of, but that are likely impeding your creative thinking in a significant way.

The Cure: Assumption Crushing™ process:

Fortunately, there is an antidote to the curse of knowledge. Assumption Crushing™ is a technique that involves consciously surfacing and challenging our hidden assumptions.

Assumption Crushing™ Step 1:

Surface your subconscious assumptions by generating a long list of statements that start with things like:

Well, in our business everyone knows…

We have to…

Our product is/does/has…

Well, of course …

We could never…

Be sure to list some really obvious, superficial, or seemingly trivial “facts,” observations, processes, etc. Sometimes breaking the obvious ones can lead to the most innovative ideas. For example, the fact that salad dressing is liquid seems fairly trivial. But breaking that assumption led to some truly breakthrough ideas.

Assumption Crushing™ Step 2:

Once you’ve come up with a long list, pick one that may not have to be true, and start to think of new ideas based on breaking that one. Then pick another and do it again. And again. You’ll amaze yourself with the innovative ideas you come up with.

Remember that the Curse of Knowledge is based on experience and expertise. Many people often assume that the best way to get new thinking, new ideas, and new solutions is to bring together a bunch of experts on the topic. But the reality is that all those experts will have a very similar set of subconscious mental frameworks. (They’ll all have essentially the same Curse of Knowledge.). A better way to generate new ideas is to invite a few experts, and then several other people with different experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. Those non-experts will help force the experts to confront and overcome their curse of knowledge.

The Curse of Knowledge is a formidable adversary that exists in our brains all the time and hinders our visionary potential. By embracing Assumption Crushing™, we can shatter the chains that confine our thinking and unlock the path to visionary breakthroughs.

Why Innovation Should Be More like Easter Eggs

Every year, Amy B., a buyer for a large retail chain store, hosts an Easter egg decorating teambuilding party, where she and a bunch of her suppliers spend an entire afternoon coloring and bedazzling boiled eggs. None of them bring their kids—they do this for the sheer pleasure of out-of-the office bonding, creating interesting and attractive objects. The group is always amazed at the creativity of the resulting eggs. (And in case you’re wondering, no, none of them are artists.)

So why, as adults, don’t people exercise their inner child-like creativity more often? And what is it about the Easter egg party that allows them to so freely generate and express such range and diversity of ideas? There are several factors—all of which also apply to innovation.

1. Each egg represents a very low commitment. It is cheap in both time and materials to try any idea they think of, so they try lots of ideas. If one doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter—it’s just one egg.

Similarly, in your innovation work, you need to consider and try out many ideas, to ensure that only the best ones move forward. As innovation projects proceed through a company, they get more expensive—in money, time, and labor—at each successive phase. Developing Fail Fast, Fail Cheap methodologies allows you to try out lots of ideas early on, while it’s still cheap.

2. They leverage not only individual creativity, but also use the power of the group. Someone will think of an idea to try, and then toss it out to the group. Then everyone contributes ideas for how best to accomplish it. No one ever says, “Yes, but that won’t work.” Everyone just thinks of ways to help make it better. The resulting final solutions are nearly always significantly better than what the person would have tried originally.

In many companies, the “Yes, But” phenomenon is all too common, and can be very damaging to creativity and innovation. Most ideas aren’t perfect when they’re first conceived, but teams act like they should be. They point out all the problems in an emerging idea before they ever attempt to find out if there’s anything good about it. For innovation and creative problem solving to thrive, it’s critical to create an environment that nurtures ideas rather than stifles them, so you get the benefit of the best thinking of the entire team.

3. They are willing to start over when something clearly isn’t working. One woman brought eggs that were not naturally white; instead, they were brown. It wasn’t clear that dyeing them would work very well, if at all. And, in fact, the first few attempts didn’t work. So, she scraped off all the color on her unsuccessful eggs several times. But when she chose red, yellow, and orange colors and left them in the dye bath long enough, she got some of the most uniquely rich and vividly colored eggs anyone had ever seen.

Unfortunately, in large organizations, too many innovation projects that aren’t quite hitting the mark proceed too far. It’s important to recognize when an idea isn’t working, and then be willing to start again when you need to.

4. Reframing the goal results in more divergent ideas. The woman with the brown eggs also tried other methods of decorating the eggs, not just coloring them with dye. Once she reframed the problem from coloring eggs to decorating eggs, everyone else also began creating the most innovative and unusual eggs of all.

This reframing of the problem is a critical step in effective problem-solving and innovation. This is because the way a problem is stated affects the potential solutions you will think of. So when addressing any obstacle, it’s a good idea to question the way the challenge or problem is worded, to see if you can reframe it to get to different and better solutions.

So the next time you find yourself with eggs to decorate—or a challenge to meet—keep these tips in mind to help you think more creatively and come up with more innovative solutions.

· Fail fast, fail cheap. Test many possible ideas.

· Leverage individual and group creativity; “Yes, and” instead of “Yes, but”.

· Be willing to start over when the idea isn’t working.

· Reframe the opportunity to expand your thinking.

The Secrets of Visionary Thinkers – Living in Possibility

We tend to believe that famous innovators or other “creative” people have some inherent quality that the rest of us don’t have. But the truth is — they don’t. They’ve simply cracked the code on how to consistently live in a possibility instead of living in obstacles.

Visionary thinkers see possibilities. Always. Most of us mostly see obstacles, most of the time. We move through work, and life, by addressing whatever next obstacle falls into our path. We problem-solve the next issue on a project, we deal with the next customer complaint, and we address the next challenge with our kids. But too rarely do we look up, survey the world, and make a conscious choice to shape our world to be the way we want it to be.

Visionary thinkers make that daily choice - to imagine the possibility of a different world, to hold on to that vision, and to refuse to let the obstacles limit their thinking. They live in possibility.

Visionary thinkers are open-minded, innovative & imaginative, willing to take risks, optimistic, and collaborative – all skills related to creative thinking. They regularly imagine, consider, and pursue new ideas and solutions.

The good news - all of these creative thinking skills are learnable! Anyone can become a more visionary thinker by learning to leverage the creative genius that’s already hidden inside.

One of the primary barriers to living in possibility is the negativity bias, a cognitive bias, or mental shortcut, that all humans share. It’s the phenomenon that negative experiences have a greater impact -- on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors -- than positive experiences do. That seems counter-intuitive, but there’s a wealth of research that proves negative affects us more than positive. As a result, we are much more motivated to avoid negative than to seek positive.

Our brains have evolved to excel at identifying potential negatives, so we can avoid them. It’s a survival mechanism, and it happens in the most primitive part of our brain – the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for detecting threats and triggering the fight or flight response. It’s laser-focused and lightning-fast at identifying potential problems. This instant identification of negatives is what can trap us into living in obstacles.

Living in possibility requires refusing to let the negativity bias rule our thinking. There are a few steps that can make a significant impact, helping us to manage around this pitfall and transform the way we think.

1. Pinpoint the problem. First, we must be able to spot when the negativity bias is at work. The easiest way to do that is by monitoring one simple phrase we say: “Yes, but….” On the surface, these words seem innocuous. And because we say them and hear them so frequently, they don’t seem like a problem.

However, this short phrase is a massive blockade to creative and visionary thinking. It dismisses any potential positives in an idea or concept, before even identifying what those positives might be. Instead, it focuses the energy and attention of both the speaker and the listeners on all the possible negatives. This can easily overwhelm any idea and immediately kill it.

2. Manage your mind. Once you’ve determined the negativity bias is at work (someone said “yes, but…”), the next step is to make a conscious choice to change your thinking. The key is to FIRST identify the potential positives in any idea, before focusing on the negatives. This sounds easy. But it’s actually quite hard. It’s counter to a basic instinct, so it really does require a conscious choice to think this way, plus very real discipline to put it into practice regularly.

3. Nix the negatives. The next critical step is to refrain from saying the negatives out loud – at least not yet. The truth is, regardless that you’ve consciously chosen to identify the positives first, your brain will subconsciously identify the negatives anyway. It’s instinctive and instant. So even while you’re enumerating positives, your brain will be busy identifying negatives, too. But the simple trick of not saying those negatives out loud will help dramatically. Force yourself to speak out loud, and write down, the positives first.

4. Teach the team. When working with others, ask them to do the same. Help them understand that letting our natural negativity bias dominate the conversation has the potential to immediately kill ANY idea. Let everyone know that, of course, there will be a time to solve the problems in the idea, but the first task is to identify the potential in the idea. If there aren’t enough potential positives, then it’s time to move to a new idea. But if the idea is visionary and can make a real difference, it’s imperative to hold off on the negativity bias momentarily and allow the brilliance of the idea to shine through.

5. Transform the troublesome term. Once the above steps have led you to a potentially winning idea, it’s time to address the problems with the idea. To continue to remain in possibility, you must change the conversation; you cannot return to “yes, but…” language. Instead, articulate the challenges as a “how might we…?” question. So, instead of saying “Yes, but it’s too expensive”, instead say “How might we do it more affordably?” This trick of flipping a problem statement into a problem-solving question is a neuroscience brain hack that will revolutionize your thinking and problem-solving. This process of identifying positive potential first is the ONLY way to find big ideas. Every successful innovation, in any industry or endeavor, is the result of someone, or a team, choosing to live in possibility in this way.

Visionary thinking requires making space for ideas that, at first, seem scary or difficult. It takes some real courage to push past our immediate “yes, but…” response and instead focus the conversation on “what if…?” If we don’t hold ourselves accountable to look for the positives, we’ll never consider nor implement any truly new ideas. Visionary thinkers must master this skill and learn to live in possibility.

The Secrets of Visionary Leaders: 5 Tips to Instantly Become More Innovative

When you have a yen for new ideas or a creative solution to a challenge, using the same tired thinking will simply lead you to the same old ideas you’ve already had or tried before. Instead, do something that will stimulate your brain and shift your perspective. Here are some ways to ensure you (and your team) shake up your thinking to cultivate the fresh ideas you need.

Change your environment. Get outside of your office. Debrief the latest research results or industry report in an art museum. Or take your team to the zoo or a local attraction with the objective of coming back with new ideas. If you can’t physically get out of the office, then find a way to get out metaphorically. Ask people to imagine how they would solve the problem at hand if they lived in another country or if viewed from the perspective of another profession.

Bring outsiders in. Invite other perspectives into your discovery and idea generation processes. For example, when thinking about retirement planning for clients, bring in other people who work with active retirees, such as travel agents or a retirement community manager. Your team will be amazed at the range and diversity of new ideas that come when they are exposed to new perspectives on their challenge. They’ll think of ideas they never would have arrived at on their own— mostly due to their own embedded assumptions about the topic.

Truly engage with your clients. Don’t rely solely on secondhand data to understand your clients’ needs. Talk with them about their lives. Go to their homes or offices to see the problems they need solutions for. All too often, teams looking at new ideas will say, “We already have ‘lots of data.’” This should always make you wary, because it usually means they have numerous reports with reams of statistics about clients. Unfortunately, it rarely means they have discovered any real new insight into clients’ needs. If you’re expecting your team to understand clients by watching a PowerPoint presentation, challenge yourself to find a more engaging and interactive process. It will be far more effective to immerse your team in real client understanding.

Question everything. Do some specific exercises that force people to confront and challenge their subconscious assumptions about the topic. An easy way to do this is to first ask for ideas that the team thinks would solve the problem but they probably couldn’t implement for some reason. Then ask them to reframe each idea by saying, “We might be able to implement this idea if …” What comes behind the “ifs” will help surface a lot of assumptions people have that may or may not actually be barriers. Of course, some of the barriers will turn out to be real, so don’t spend more time on those ideas. But in every case that I’ve ever done this with client teams, they also discover many supposed barriers that they could solve.

Let some crazy in the room. The academic definition of creative thinking is “the process of coming up with new and useful ideas.” The only way to get new ideas is to start with seemingly crazy ideas. Every truly innovative idea seems a little crazy at first. If you only start with ideas that are comfortable or clearly easy to implement, they’re probably not very new. So, encourage people to throw in extremely wild ideas. Then, play “If we could.” Instruct the team to temporarily let go of the problems in the idea and ask, “If we could implement this idea, what would be the benefit(s)?” Once you have identified the benefits of each crazy idea, narrow it down to the most promising few and ask the team to look for viable solutions to the barriers.

A team I worked with was on the verge of killing a truly original idea for a new kids’ cereal because they didn’t know how to create the critical component. However, after “If we could,” they agreed the idea was so interesting and unique that they needed to explore it. The research and development team made a few calls to other experts, and within a few weeks they solved it. This idea resulted in the most successful new product launch in the brand’s history!

It is unfortunately all too easy to simply approach every new challenge using our typical day-to-day thinking. It feels familiar. It’s easy to access that type of thinking, and it works on most daily challenges. So, you subconsciously assume it will work on any challenge. It’s incredibly helpful to do some meta-analysis on your thinking. In other words, think about how you’re thinking. Not every problem will benefit from the same type of thinking. Once you recognize that this new situation needs new thinking, it’s easy to shift to a more productive mode for this particular challenge. Then shift back to the more familiar day-to-day thinking for your daily tasks.

Finding the Hidden Innovators in Your Company

Most people who work in a corporate environment are familiar with some type of personal style indicator — Meyers Briggs Type Indicator, Strengths Finder, DISC profile, and many others. However, there’s a less well-known one that’s particularly relevant and useful in innovation and it is specific to your creative thinking style.

At the heart of creativity and innovation is problem-solving. Since all humans problem-solve, by definition, all humans are creative. However, we each go about our problem-solving in our own preferred style, and society has come to label only one style as being “creative” – the style called “Innovator” on this assessment.

Think of Leonardo da Vinci as an extreme example of that Innovator style. He was an idea machine, constantly jumping around in numerous disciplines—including art, cartography, anatomy, botany, astronomy, geology, and others. Many of his ideas were truly ground-breaking. He conceptualized a helicopter, a tank, a calculator, and concentrated solar power. He even outlined a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics.

Thomas Edison is a great example of a creative thinker with an Adaptive style. He held more than 1,000 US patents. However, many of the products he patented, perfected, and commercialized were not originally conceptualized by him. For example, he did not actually invent the light bulb, he developed a light bulb that was practical. He was able to improve, fix, optimize, and operationalize ideas better than perhaps anyone else in history.

Creativity Style Characteristics

It is important to note that your thinking style is an indicator of preference, not of ability. Any of us can think and behave in another style—and we all do it effectively when we recognize it’s needed. But we go back to our preferred style as soon as we can. It’s where we’re most comfortable and probably where we’re most consistently successful.

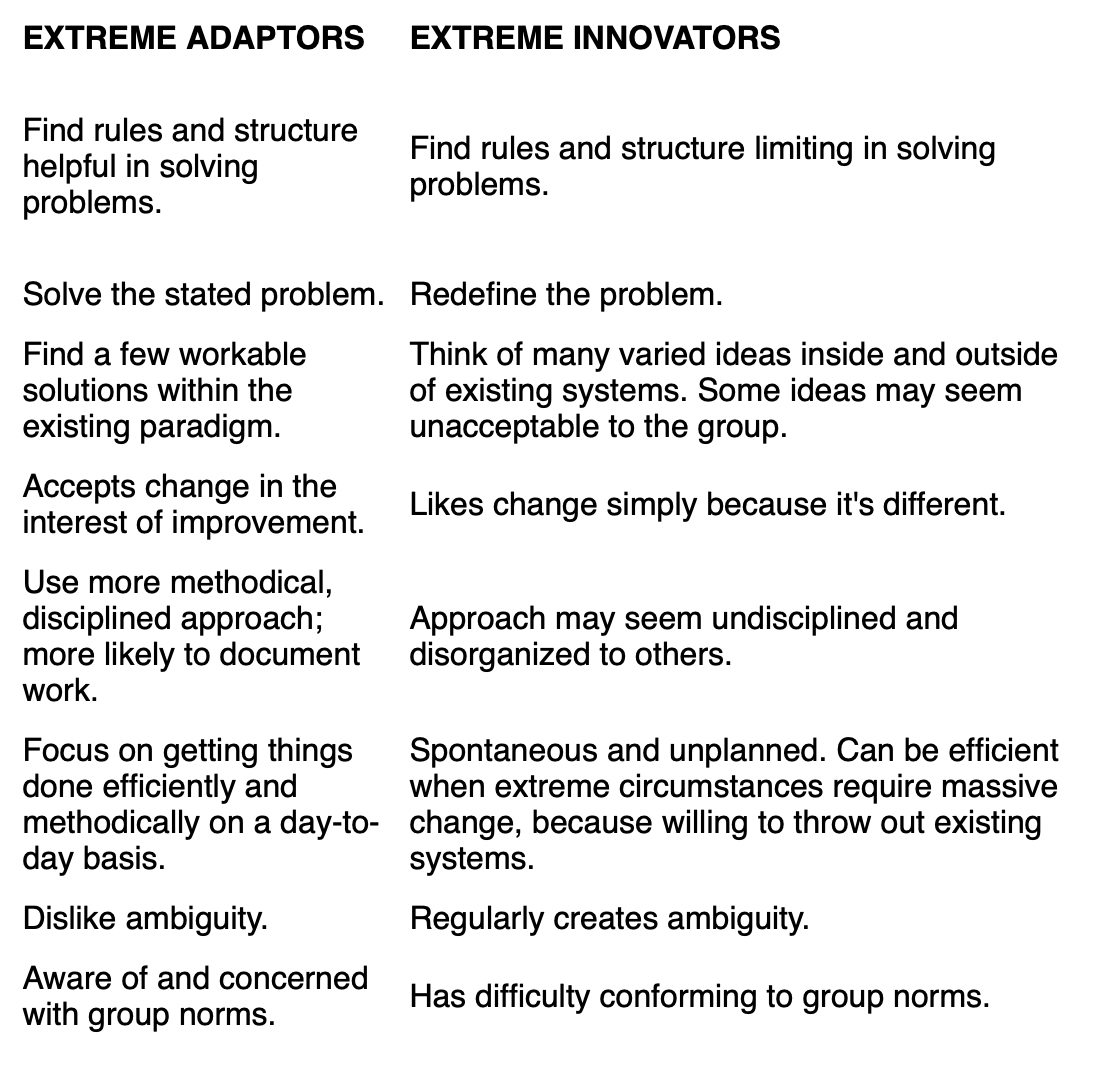

The chart below illustrates some key traits of extreme Adaptors and extreme Innovators.

The important question becomes - who should you have running your innovation projects?

Extreme innovators are great at coming up with ideas, and their energy and passion for ideas may get other people excited about them, at least at the beginning. But then their greatest strength – their zest and constant quest for new ideas - becomes a weakness that starts to create problems. In short, they’ll drive everyone on the team crazy and jeopardize the success of the project. So, an extreme Innovator may not be the person you want to run the show. They’re one of the actors, and probably a lead actor, but they shouldn’t be the producer.

So, if it isn’t that person, the next logical conclusion might be that the extreme Adaptors should manage the process. They’re organized, disciplined, and efficient. But similarly, their strengths can also become weaknesses at the extremes. High Adaptors’ discomforts with ambiguity will likely result in attempting to define the scope of projects too early, or kill them altogether if the ambiguity can’t be resolved quickly. And their focus on the stated problem may prevent them from seeing solutions or opportunities outside their day-to-day world.

So now what? If you’ve ruled out extreme Innovators and extreme Adaptors as the best candidates for managing the process, where does that leave you? With everyone else. Here’s the great news: everyone else is most of us. 67% of the population is in the middle of these 2 extremes.

If you want someone who may be naturally inclined to manage an innovation process, pick someone more in the middle, who can be a Bridger. The benefits of a Bridger in this role are numerous because they naturally exhibit moderate traits of both adaption and innovation. So with a Bridger, you get a bit of the best of both.

They “get” the vision of the big idea that the extreme Innovator came up with. They’ll get excited and energized about ideas. They can live with ambiguity for a while. But they also see the need for organization and documentation. They’ll understand the challenges that will have to be solved in order to implement that big idea. They can stay focused and see projects through to the end. They’ll understand group norms and will bridge the communication gap between the high Innovators and the high Adaptors on the team.

The problem may be in getting these people to understand that they are the ones who should be running the innovation process. Since they’re not high Innovators, they haven’t had people telling them their whole lives that they’re creative thinkers. So they may not think of themselves as a good fit for innovation.

The role of those responsible for innovation in your company should be to convince the “everyone elses” in the middle that they’re needed in the innovation process—and help them see how their unique contributions can be incredibly valuable in this arena.

A Quick Creative Thinking Tip

Harvard’s social media manager asked me for a quick creative thinking tip. Here’s a 2 minute video with a thinking tool that will instantly help you generate more creative ideas for any challenge.

How to Sustain Flexible Thinking and Nimble Action that Emerged from the Pandemic

To survive the pandemic, companies were forced to adapt very quickly to radically new circumstances. Even large organizations - where it’s typically difficult to shift directions quickly - managed to accomplish it. Leaders discovered that, when required, their organization could act much more quickly and nimbly than they normally do.

So the obvious questions become:

1) What was different? and;

2) How can we “hardwire” this flexibility into the organization so we continue to be stronger in the future?

What was different?

To understand what was different, we first have to dip our toe into neuroscience. All humans have a set of cognitive biases, which are mental shortcuts that we use for problem solving and decision making.

To be clear, cognitive biases are NOT individual or personal biases. They are a neuroscience phenomenon that all humans share. Meaning, it’s not that I have one and you have another; we all have all of them. It’s also important to understand that they operate subconsciously; we’re not aware when we’re relying on them. So they affect our thinking in ways that we don’t realize.

Cognitive biases grow out of the way our brain functions. We have two different thinking systems, commonly known as System 1 and System 2, sometimes referred to as thinking fast (1) and thinking slow (2).

System 1 is the “intuitive”, quick, and easy thinking that we do most of the time. In fact, it accounts for about 98% of our thinking. It doesn’t require a lot of mental effort; we do it easily, quickly, and without having to think about that fact that we’re thinking.

System 2 thinking is deeper thinking; the kind that’s required for complex problem solving and decision making. This deeper thinking requires more effort and energy; it literally uses more calories. Since it’s less energy efficient, our brain automatically and subconsciously defaults to the easier System 1 thinking whenever it can, to save effort.

Cognitive biases result when our brain tries to stay in System 1 thinking, when perhaps it should be in System 2. The outcome is often poor decision making or sub-optimal solutions. But we don’t realize that we have sub-optimized because all of this has happened subconsciously.

Under normal circumstances, there are a variety of cognitive biases that typically cause us to change slowly, cautiously, and incrementally. Here, we’ll discuss 3 of them.

The Negativity Bias

Negativity Bias is the phenomenon that negative experiences have a greater impact on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors rather than positive experiences. So we are much more highly motivated to avoid negative than we are to seek out positive. The way this manifests in our daily work is that we are much more prone to reject new ideas than to accept them, because rejecting ideas feels like we’re avoiding potential negative. The most common response to any new idea is “yes, but….”, with all the potential problems following the “but”. Our brains are laser focused and lightning fast at identifying potential problems.

The Status Quo Bias

The Status Quo bias is a subconscious preference for the current state of affairs. We use “current” as a mental reference point, and any change from that is perceived as a loss. As a result, we frequently overestimate the risk of a change, and dramatically underestimate the risk of “business as usual.” History is littered with examples of companies that have gone out of business by failing to recognize that change is needed until it was too late.

The Curse of Knowledge

In any subject where we have some expertise, we also have many subconscious assumptions about that subject. Under normal circumstance, this Curse of Knowledge (these latent assumptions) limits our thinking and suppresses our ability to come up with radically new ideas.

The Intersection

In typical circumstances, these three cognitive biases (and likely others) conspire to make us perceive that continuing as we are - with only slower, incremental changes - seems like the best decision. It feels familiar, it feels lower risk, in sum – it feels smarter. Choosing to do nothing different is – very often – simply the default. It often doesn’t even feel like we made a decision; it feels instead like we were really smart for NOT making a potentially risky decision.

But during the pandemic, changing nothing was simply not an option. This particular situation was so unique that our brains didn’t have the choice to stay in short-cut System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking was required. Since our brains were literally working harder -in System 2 - all the cognitive biases weren’t a factor. We couldn’t reject new ideas. We couldn’t maintain the status quo. We had no Curse of Knowledge to limit our thinking.

How to Continue to be More Nimble in the Future

The key to maintaining flexible thinking and nimble behavior is to not allow our brains to fall into the trap of cognitive biases. Obviously, since these are intuitive and subconscious responses, this is not easy task. But there are proven ways that we can better manage our brains. Here are a few ways to start.

1. Short circuit the Negativity Bias. Respond to “yes but…” with “what if…?” This requires a dedicated and conscious mental effort, by everyone on the team, to monitor their own and the team’s response to new ideas. Every time “yes, but…” is uttered, the response needs to be “What if we could solve for that?” This reframing of the problem into a question will trigger our brains to look for solutions, instead of instantly rejecting the idea.

2. Mitigate the Status Quo Bias. When weighing a choice of possible actions, be sure to overtly list “do nothing” as one of the choices, so you are forced to acknowledge it is a choice. Also include “risk” as one of the evaluation criteria and force the team to list all the possible risks. Then comes the difficult part - remind them that their subconscious brain is making them perceive the risks of doing nothing to be lower than the reality, so they should multiply the possibility of each of those risks.

3. Curtail the Curse of Knowledge. Rely on advisors who don’t have the same Curse of Knowledge. In other words, seek out advice from people outside of your industry. When evaluating ideas or actions, these outsiders won’t have the same blinders that you have, so they will likely have a more clear-eyed view of the benefits and risks.

The bad news is that cognitive biases are always going to be a factor in our problem-solving and decision making; they’re hard-wired into us. The good news is that, with some dedicated and continuous mental effort, we can mitigate them and become more nimble in the face of change.

Let Some Crazy In the Room: How to get More Breakthrough Ideas. Interview with Pete Mockaitis of How To Be Awesome At Your Job

Thrilled to be a guest on the How to Be Awesome At Your Job podcast with Pete Mockaitis! Click the title above to listen.

Market Changers Avoid Blind Spots

My friend and colleague, Mike Maddock, writes about innovation for Forbes magazine. He interviewed me for an article on how to get around some natural limitations we all have on creative thinking.

How Your Own Brain Limits Your Thinking (and What To Do About It)

Why is it that coming up with truly new and different ideas for our business (or our lives) can sometimes seem difficult? The answer is based in neuroscience.

All humans have cognitive biases, or mental shortcuts, that we use for problem solving. These cognitive biases operate unconsciously, so they limit our thinking in ways we’re not aware of.

In his book “Thinking Fast and Slow”, Daniel Kahneman describes that our brains have two types of thinking, and we actually can’t utilize them both at the same time. We constantly toggle back and forth between the two.